Kimberly Himmer presented this paper at ITEC 2018 . Contact us if you’d like to learn more about our design process for workforce training, and how we can help you harness the power of andragogy!

********************************************

Game On!: Optimizing Training for Today’s Workforce

Abstract

Many computer-based training enterprises marketed to militaries and government agencies today are failing to engage personnel for one very simple reason: they are designed using pedagogical principles instead of andragogical principles. Children and adults learn in very different ways; as a result, the designers of these training platforms need to be better focused specifically on how adults learn. By understanding exactly how adults learn, one thing becomes very clear: game-based training is an optimal medium for adult learners, because the way in which games operate naturally aligns to the principles of andragogy. This paper lays out the argument by discussing: pedagogy versus andragogy; how and why many of our current training offerings are ineffective at reaching adult learners; the limitations of simulations; the characteristics of games, and how they operate as complex, emergent systems; and how and why game-based training operates effectively as a platform for adult learning.

Keywords

game-based training, Serious Games, andragogy, games vs. simulation, adult training and education, military training

Background

There is a robust body of evidence illustrating that current formats of online learning are not engaging learners in the ways that educators had originally envisioned. Ninety percent of online learners fail to complete a course that they voluntarily signed up for (Tauber, 2013). The reason for this is that the instructors designing these courses are framing the lessons as if it is being delivered in a traditional classroom (Tauber, 2013). Even the U.S. Navy has acknowledged the shortcomings of its online training courses; as of April 2017, it no longer requires sailors to complete General Military Training requirements online. The reason: the current format of “online training is ineffective and impersonal” (Faram, 2017).

And it is not just the United States that is recognizing the shortcomings of Computer-Based Training (CBT). Research conducted by Commander Geir Isaksen of the Norwegian Defence University College echoes similar sentiments. In a series of studies he conducted between 2014 and 2016, he found that most students came to CBT courses voluntarily and with a high degree of motivation to learn, but became quickly unmotivated either due to the instructor, or instructional design. One of the main conclusions of his research is that learner motivation is directly tied to the method though which the information was provided; and that “motivation influences engagement, cognitive efforts and thereby affects the ability to process information and construct knowledge” (Isaksen, 2016 ). Therefore, if the training cannot retain the adult learner’s motivation, then no learning is taking place.

Even simulated environments are not the training panacea they were once thought to be. Research conducted in 2014 by Heather Walker, from the U.S. Naval Air Warfare Training Systems Command, and Robert Wray, from the U.S. Army Research Institute, shows that while the military is using more immersive virtual environments to conduct training, these environments are spaces in which to practice skills and knowledge acquired through other media. For example, a U.S. Army program of record, created by Bohemia Interactive called VirtualBattleSpace2 (VBS2) is a commonly used virtual platform to train soldiers before deploying to overseas combat locations. However, VBS2is actually a simulator; it is not a game-based learning environment. This research, conducted by Walker and Wray, highlighted the fact that programs such as VBS2 allow participants to practice skills learned through other means; and that there is no learning imparted by those programs (2014). And their research specifically highlights the fact that the feedback system is missing in these simulated environments (Walker and Wray, 2014). If someone is practicing in a simulator, but completing the tasks incorrectly, he will only reinforce the incorrect actions, and fail to learn the correct way to complete the task.

However, the U.S. defense sector is slowly starting to look at game-based training as the natural evolution from simulators. Research has shown greatly increased learning outcomes from game-based learning. For example, as part of their 2014 research, Walker and Wray conducted an experiment with two groups of military officers: one learned strategic decision-making skills in the classroom and then practiced it on a computer-based simulator; the second learned the skills through a game. They found that the group that learned experientially through gameplay performed significantly better than their practice-only counterparts (2014). Walker and Wray concluded that the practice-only group which used the simulator was unable to self-diagnose and correct their errors, and that they made significantly more errors than the game-based learning group (2014): the practice-only group made an average of 14 errors, compared to an average of two errors by the game-based learning group (2014). And, while not a specific focus of the research study, their research also highlighted the executive-level cognitive benefits that game-based learning also provides. The game-based learning group performed significantly better in more complex scenarios that were not specifically practiced by either group (2014). This research highlights the shortcomings of current training programs, and illustrates the real potential for game-based training.

The reason why many of these programs fail to reach their training audience is because they adhere to standard pedagogical principles; however, adults and children learn in very different ways. Malcolm Knowles, one of the world’s leading researchers on andragogy, determined that adults did not appreciate being taught like children, and that they frequently resisted any form of training that adhered to pedagogical principles (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 2005). Pedagogy, as an educational model, was developed by monks in the Middle Ages, in order to “develop children into obedient, faithful, and efficient servants of the church” (Knowles et al., 2005). The teacher is in control of the entire educational evolution, and determines the success or failure of each student. The information is didactically provided. Grades or other external factors drive student motivation, along with the expectation that the information being learned will be of some future use to the student (see Table 1). Unfortunately, the vast majority of computer-based training enterprises used in the military and in industry are still designed using these pedagogical principles. As a result, workers generally loathe having to complete these required training programs, just as Knowles determined through his research. For example, junior officers in the U.S. Navy’s SWOS-at-Sea training pipeline, which heavily utilized CBT, “did not find the CBT engaging, interactive, or interesting… ‘Death by PowerPoint’ was a common complaint” (Bowman, Crawford, & Mehay, 2008).

Table 1: Pedagogy versus andragogy (Knowles, 2005)

Andragogy, on the other hand, operates on an entirely different set of principles; it is grounded in the adult’s life-long necessity to learn. According to Knowles, the adult learner: is self-directed; has a reservoir of prior knowledge and experience with which to relate new learning; desires to learn experientially; is motivated to learn out of responsibility for his social role, as opposed to academic pressure; and wants to learn new things that are immediately applicable to his current situation (Knowles, et al., 2005) (see Table 1). Adult learning is problem-centered, not subject-centered (McClelland 1970); and that is where the vast majority of our training enterprises are failing the adult learner. These training programs should be focused on the efficacy of the learning process, not the efficiency of the teaching process. Games are actually an ideal medium for adult training, due to the fact that the way in which games operate inherently aligns to the ways in which adults learn. And by understanding what constitutes a game, it becomes clear how games align with the principles of andragogy.

Games and Andragogy

Games are defined by the fact that they have goals, rules, implements, a feedback system, and voluntary participation. Games are also fictional; the game world may look like the real world, but the player never enters a game assuming the rules of the game world mirror those of the real world. This provides a sense of ambiguity, which is inherent in all games. This ambiguity sets the stage for the problem-solving which players naturally undertake, and positions the players with volition and agency within the game world. Finally, games provide players with a safe space for creativity and experimentation; and this allows for failure to be reframed as progress. Only by failing can the player learn how to correctly solve a problem. As a result, the act of playing the game becomes an act of learning. It is exactly because of these traits that games are so effective at training, and naturally align to andragogical learning principles.

Much early research into game-based learning showed games to be an ineffective training platform (Prensky, 2001). However, it had nothing to do with the platform; it was precisely because they were just bad games (Prensky, 2001). For example, taking a current popular game and “reskinning” it with the façade of a training topic and some learning objectives does not make an effective training game. Reskinning Angry Birdsto teach soldiers about cultural property protection (CPP) is highly unlikely to result in the transferal of knowledge regarding CPP. Furthermore, $25,000 Pyramidand Jeopardy spin-offs with a database of training questions do notconstitute game-based training. The learning objectives must be inherent within the system of the game itself. That way, the problems that the player is solving, and the tasks he is accomplishing in the game world, will intrinsically be aligned with the learning objectives the game is trying to impart. The learning objectives must bethe system; and this system must be complex, and emergent.

Games as Self-Directed, Experiential Learning

Because games are fictional, they always possess a degree of ambiguity when a player first enters. While games may look like the real world, the player never enters into the game assuming all of the rules directly mirror that of his world. This ambiguity helps create a productive learning environment, because the player must be open to learning more about the game world he has just entered. As a result, games are exploratory spaces, which also appeals to the adult learner. By giving the player latitude to explore the game world however he chooses, it appeals to the players need for agency and volition. This characteristic of games aligns with andragogy because, as discussed earlier, the adult learner needs to self-direct his learning experience; he does not want to be spoon-fed. The non-teleological characteristics of games gives the adult learner the ability to write his own learning narrative; it is not dictated to him. The adult learner wants to feel that he has some control over his learning experience, and has the freedom to explore a topic in a way that makes sense to him.

Some key defining characteristics of games is that they have goals, rules, and implements. It is up to the player to figure out how to use the given implements, in accordance with the delineated rules, in order to achieve the goals of the game. As a result, games naturally create an active learning environment for the adult learner where he must dothings in order to advance. As a result, games are naturally platforms for experiential learning and problem-solving; only by accomplishing a series of goals can the player advance in the game world, and eventually achieve a win state.

Self-Evaluation through Constant Game Feedback

The adult learner, as Knowles’ research shows, needs a constant feedback loop within his learning experience, so that he can self-evaluate his learning and growth. He does not want to study all week, and then find out when he gets his test back that he sorely misunderstood the course content. He wants to internalize his learning and ensure that he is actually gaining the skills and knowledge he desires to attain. Aligning with this andragogical principle is the fact that games inherently have a feedback system; it is a defining trait of games. For example, the heads-up display of popular first-person-shooter games provides the player a variety of feedback, in real-time, throughout the game. He will know, for example: the status of his health; the number of rounds in each weapon; the direction and distance to enemies; the direction and distance to his objective; and the time remaining to reach that objective. Because of this, the player has a constant method to evaluate his progress in the game, as well as his overall strategy. The adult learner needs this same type of feedback in order to evaluate progress and learning strategy, in order to alter course accordingly to accomplish his desired learning goals. This gives him a sense of control, and also a sense of accomplishment. Throughout the experiential learning process, the learner must be allowed to formulate a hypothesis, and then accept or reject the results based on the consequences of his action (Knowles 1970). Knowles likens this to the “feedback mechanism” in a guided missile. The missile constantly corrects any “deviations from [its] course while in flight on the basis of data collected… and fed back into the control mechanism” (Knowles 1970). This same method of constant, iterative feedback is what the adult learner craves.

Intrinsic Motivation in Games

The final principle of andragogy highlights the fact that the adult learner is intrinsically motivated to learn. The adult learner is exercising his own volition and agency by deciding to learn a new topic; just as the player in a game exercises his volition and agency throughout the process of playing a game. As highlighted earlier by Isaksen’s research, learner motivation is key to cognitive effort and, therefore, is critical to the successful construction of knowledge. With games, the motivation to continue to play, and therefore continue to expend cognitive effort, comes from several sources: that feeling of control that playing provides; the process of learning the system of the game through gameplay, and the challenge that it provides; and the feeling of satisfaction from being productive in the game world. As game designer Jane McGonigal writes, in the game world “having a clear goal motivates us to act… and actionable next steps ensure that we can make progress toward the goal immediately” (2011). This guarantee of productivity motivates the player to continue, even when faced with progressively more difficult challenges.

Another source of player motivation comes from the fact that humans make meaning through play. Games satisfy both cultural and biological functions. As cultural historian Johan Huizinga wrote, “All play means something” (1949). Play is the way in which we as a species make sense of the world around us, and it is how we—in turn—make meaning within that world. It serves as an organizing function not only in our culture, but to humans on an individual level as well. According to Dr. Stuart Brown, who has dedicated his career to studying the science of play, “…[h]umans are the biggest players of all. We are built to play and built through play” (2009). As Brown writes, “researchers from every point of the scientific compass” can all agree that play is a profound biological process. It has evolved within most animal species, and has actually shaped the functioning of the brain, “mak[ing] animals smarter and more adaptable” (2009). So in essence, evolution has shaped the way we play; and play, in turn, has also shaped the way in which we have evolved as a species. It is scientifically proven that humans learn through play; therefore, training games need to capitalize on this anthropological fact.

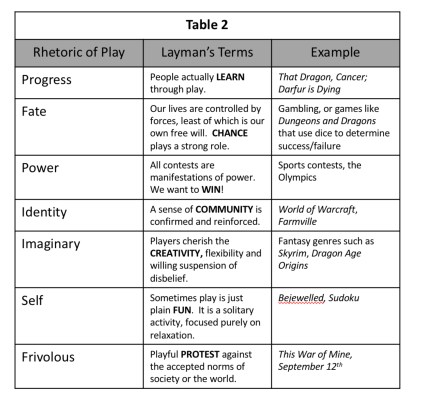

An additional, and nuanced source of player motivation also comes from understanding the variety of ways in which people play. Certain types of games naturally appeal to certain types of people. Some people like to play strategy games such as Risk; others enjoy fantasy role-playing-games such as Dungeons and Dragons. That is because different games and modes of play are cognitively energizing to different people. Training games must capitalize on this knowledge, in order to be appealing– and therefore teach– its target audience. Play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith, in his book, The Ambiguity of Play, described what he calls the seven “Rhetorics of Play,” which give valuable insight into how people make meaning through play; it taps into their emotions and belief systems. This is howgames internally motivate their players, and this is why people are naturally drawn to certain types of games over others. As a result, utilizing this knowledge can make training more effective by understanding how the target audience of any training game makes meaning. Furthermore, games do not have to fall solely into one rhetoric over another, it is possible for a game to encapsulate elements from several of these rhetorics. The resulting game will then appeal to a much broader training audience. Table 2 outlines Sutton-Smith’s Rhetorics of Play, and defines them in layman’s terms. Additionally, there are examples of games that utilize each of these rhetorics.

Table 2: Sutton-Smith’s Rhetorics of Play and definitions (1997), and examples

People enjoy playing games for a variety of reasons. As Table 2 illustrates, “fun” is only one reason people play. Game designer Jane McGonigal writes, “Games make us happy because they are hard work that we choose for ourselves, and it turns out that almost nothing makes us happier than good, hard work” (2011). Games are work; and people enjoy playing because of the feeling of accomplishment that games provide. By fully harnessing the psychology of play in training games, today’s workforce will be more motivated to participate, which will create the cognitive conditions necessary for learning to take place.

Games as Complex, Emergent Systems

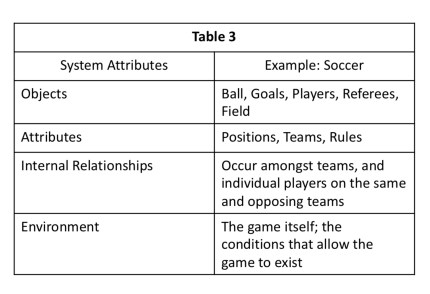

The characteristics of games, which naturally align with the andragogical principles outlined above, are a result of the fact that games operate as complex, emergent systems. Emergence in a system is the product of “coupled, context-dependent interactions;” and these are critical to creating meaningful gameplay (Salen & Zimmerman 2004). For example, one can list and describe the rules of a game; however, one cannot list all of the results that set of rules will produce (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004). The whole is greater than the sum of its constituent parts; that is emergence. For example, by analyzing the game of soccer, its characteristics as complex and emergent become evident. A system has: objects; attributes; internal relationships; and an environment (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004). Table 3 outlines soccer as a system.

Table 3: The game of soccer as a system

And soccer, as a game, is an emergent, complex system because no two soccer matches are the same—even between the same teams. That is because the system evolves and changes according to the situations within the game itself. The recursive application of the rules by objects within the system changes the internal relationships of those objects (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004). Furthermore, those relationships are always context-dependent; an action within the system does not result in the same output from the system every time. It depends on what other objects are doing within that system at any given moment. The resulting system is non-linear, which provides the game environment with the ambiguity that is so critical to– and characteristic of– games.

Because of the way that games operate as a system, they naturally lend themselves to being a good platform for adult learning. Agents within the system of a game are autonomous, whether those agents are the player(s) or other non-playable characters (NPCs). While NPCs are coded into gameplay, they each have their own set of rules that govern their actions. And as a result, they take actions in relation to other game agents, and therefore are not entirely predictable. And even the player, while governed by a set of constraints, still has the ability to self-direct his actions within the game world. In a learning game, it gives the player the ability to make decisions and take actions, and then analyze the resulting output of the system.

Because the game world is fictional, the player learns through playing. He learns how the game world operates; but most importantly, he learns which actions to take in order to create the conditions within the system for emergence to occur. When this happens, the system itself changes and results in the achievement of a desired goal. By setting the conditions for the creation of these complex interactions, the player learns. This is why the learning objectives must be intrinsic to the system of the game; because this, on a formal level, is the site of learning in game-based training. And it creates the experiential learning and problem-solving that adult learners desire.

Furthermore, the formal system of the game is always providing some type of feedback to the learner. He sees the results of his actions, and determines whether or not they created the desired outcome. The feedback loop is intrinsic to the system of a game. In the example of a soccer game, players do not have to be told from an outside entity if their actions are creating the desired system output. If they are missing passes, and are spending more time in their defensive end of the field, they are being provided with useful feedback from the game itself. And with that feedback, the players will change their actions in an effort to create the conditions to score a goal. As discussed earlier, feedback is essential to the adult learner, and the system of a game naturally provides that to the player.

Finally, internal motivation is a key andragogical principle; the adult learner must remain motivated within the learning environment in order to construct knowledge. The formal elements of a game that create this motivation are directly tied to the ideas of complexity and emergence within the system. Even on a formal level, games are engaging because they make meaning. According to Salen and Zimmerman,

Meaningful play in a game emerges from the relationship between player action and system outcome; it is the process by which a player takes action within the designed system of a game and the system responds to the action. The meaningof an action resides in the relationship between action and outcome (2004).

As discussed earlier, people make meaning through play. And within the system of a game, the complexity of the relationship, and the emergence that occurs, actually create that meaning; therefore, they create player motivation. Well-designed games naturally create that experience for the player. Therefore, well-designed training games naturally create that motivation for the learner.

Conclusion

Training games have often received a bad rap over the preceding twenty years as being ineffective. However, it has nothing to do with the fact that they were games; it has everything to do with the fact that they were just really badgames. And in some cases, they may have been called games, but were not. They did not possess the characteristics of a game, nor the requisite formal complexity that makes a game effective and engaging for its players. However, games that are designed properly can be an effective form of training for the adult learner because games naturally adhere to the principles of andragogy.

Games are engaging because they provide agency and volition to the player in the game world. They provide a safe space for creativity, experimentation, and failure. However, through failure, the player learns the correct way to complete a task and achieve his goal. As a result, failure is positively reframed; the act of playing is an act of learning. Game-based training appeals to the adult learner naturally, because it directly aligns with the ways in which adults learn. The adult learner wants to be in control of his learning experience; he enjoys problem-solving and learning experientially; he desires constant feedback so that he can assess his learning experience and course-correct when necessary; and he actively seeks learning experiences out of desire to better himself.

Current computer-based training enterprises are failing to engage the adult learner; therefore, it is time to change the game. Learners have complained for decades about the ineffectiveness of computer-based training. They are not motivated, and are therefore not retaining the material. It is easy to blame the trainee for their lack of motivation and lack of material retention; however it is not their fault. Training needs to be focused on the learner’s needs, not what is easiest for the teacher. Decades of research illustrate how adults learn best—and it is not in a classroom lecture. Games, however, are an optimal medium for training, because they naturally align with the ways in which adults learn.

References

Bowman, W., Crawford, A., & Mehay, S. (2008). An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Computer-based Training for Newly Commissioned Surface Warfare Division Officers. (Report No. NPS-HR-08-140). Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil.

Brown, S. (2009). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. New York, NY: Penguin.

Faram, M. (2017, March 27). Navy eliminates online GMT—mandatory training shakeup puts commands in charge. Navy Times Online. Retrieved from http://www.navytimes.com.

Huizinga, J. (1944). Homo Ludens. London, UK: Routledge, & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Isaksen, G. (2014). Hey, Your e-learning courses are giving me a cognitive overload. Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation, and Education Conference; Orlando, FL; December 2014. Retrieved from http://www.iitsecdocs.com.

Isaksen, G. & Hole, S. (2016). How to evaluate student motivation and engagement in e-learning. Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation, and Education Conference;Orlando, FL; December 2016. Retrieved from http://www.iitsecdocs.com.

Knowles, M. (1973) The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

Knowles, M., Holton, E., & Swanson, R. (2005). The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. Burlington, MA: Elsevier.

McClelland, D. (1970). Toward a Theory of Motive Acquisition. In M. Miles & W Charters (Ed.). Learning in Social Settings(pp. 414-434). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is Broken. New York, NY: Penguin.

Prensky, M. (2001). Computer Games and Learning: Digital Game-based Learning. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu.

Salen, K. & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Tauber, T. (2013, March 21). The dirty little secret of online learning: Students are bored and dropping out. Quartz. Retrieved from http://www.qz.com.

Walker, H. & Wray, R. (2014). Effectiveness of Embedded Game-Based Instruction: A Guided

Experiential Approach to Technology Based Training. Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation and Education Conference; Orlando, FL; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.iitsecdocs